I’ve been spending a great deal of time thinking about what it means to be and feel Korean/Asian American in this country. As I read about the horrific incident at Spring Valley High and responses from apologists, I can’t help but wonder about the ways in which Korean-Americans are complicit in the demonization and oppression of our black and brown brothers and sisters. How can we can tangibly understand that our own empowerment is contingent upon the empowerment of (all) Others?

The U.S. not only has a long history of systemized racism, but also an old tradition of cleverly pitting oppressed groups against one another. When low-income black students “act out” in school, or perform poorly, they are compared to their “industrious” and “obedient” yellow counterparts without consideration of the many institutionalized differences between the communities (e.g. following passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 and the liberalization of the U.S. national quota system, a larger number of highly educated and professional Koreans moved to the country, meaning many of the folks coming over had certain types of privilege that were decidedly unavailable to many low-income people of color already in the country or migrants from “less desirable” countries).

Today, I’m writing about Chinese immigration to Mississippi in the first installment of my new series “Our States, Our People, Our Food.” Of course, I don’t and can’t speak for Chinese communities, but I can make observations about both their incredible fortitude, and also the ways in which they benefited from social distancing from the black community.

Beginning in the mid-1800s, a number of Chinese immigrants were “shipped” to the American South from Cuba as a new source of cheap labor (though most arrived between 1910-1930). Following the Civil War and Reconstruction Era, white landowners were suddenly struck with the responsibility of paying for labor (poor them!). Many opted to hire cheap migrant laborers, likely to undermine the growing political power of freed black people. According to an article by Vivian Wu Wong called “The Chinese in Mississippi: A Race In-Between,” many southerners believed that utilization of Chinese immigrants would strengthen “white political power by displacing voting Negroes: for the Chinese…would not vote.” Good job, white people.

Historians say that initially, the Chinese were treated as poorly as black people – they were, after all, meant to displace black sharecroppers (though I think this is probably arguable). Initially, most migrants were men who came to supplement family income. They came to the U.S. not to settle, but to earn money to send to their families. This is important, because the Delta region wasn’t originally meant to be their home – therefore, economic success was more crucial than social and racial equity. After working on plantations and railroads, they turned to another activity – opening and running grocery stores. The first Chinese grocery store in Mississippi likely appeared in the early 1870s, and provided the community with some financial success. Black businessmen could not open similar businesses because they lacked the resources to start their own businesses, and wholesalers refused to give them credit because…racism. It’s important to keep in mind that most immigrants were coming from Sze Yap, a district in south China that was more commercially sophisticated than many other parts of the country, with a history of contacts with foreign traders. Anywho, Chinese grocery stores were small, one-room shacks which carried only a few basic items, and the main clientele was mostly poor black laborers.

After Chinese men established their grocery stores, they would often send back home for a young male from their family to come and help the business succeed. This made for a strong thread of familial migration to Mississippi, and helped the community gain some economic success. According to an article entitled “Chinese in Mississippi: An Ethnic People in a Biracial Society” in Mississippi History Now, “For generations, grocery stores would be passed down from father to son, and as of the late 1970s, six family names accounted for 80 percent of the Delta Chinese population.”

The Pang family in Mississippi, early 1920s (taken from https://abagond.wordpress.com/2014/06/06/chinese-americans-in-the-deep-south-after-1882/)

The relationship between the Chinese grocers and the black members of the local community grew over the years. Not only did the Chinese run businesses in black neighborhoods, but also lived there. It could be argued that these stores were successful largely because they provided an alternative for black consumers – they no longer had to go to white stores (if they even could) only to be disparaged and disrespected. Additionally, some Chinese men married black women, and were integrated into the black community in a way they were not with whites. However, once these immigrants decided to make Mississippi their long-term home, they were no longer satisfied with their racial in-betweenness, and demanded more (especially access to quality, white education).

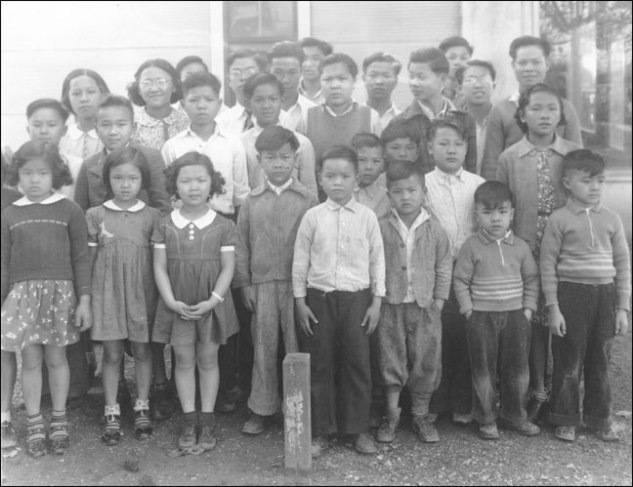

Students of the only all-Chinese school in Bolivar County, Mississippi, 1938. Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History (photo taken from http://mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us/articles/86/mississippi-chinese-an-ethnic-people-in-a-biracial-society)

By law, Chinese people were considered a “colored race,” and were legally excluded from attending schools that were meant for only white people. Chinese parents refused to accept this, and had some financial means for leverage. Vivian Wu Wong explains that the white community was probably not as concerned about admitting Chinese children to the schools as they were about admitting black children, and since there were some Chinese/black interracial children, whites decided to emphasize the importance of Chinese racial purity. Thus began Chinese community’s practice of socially distancing itself from black people. Vivian Wu Wong argues, “To respond to this fear which they saw as the main obstacle in their struggle for quality education for their children, leaders in the Chinese community made a choice. Rather than challenge racism, they distanced themselves from the black community.” They believed that as soon as they could prove their separateness from black people, whites would be willing to accept them and invite them into their superior educational institutions.

Following this sad and tragic rejection of the black community, the image of the Chinese in Mississippi slowly changed. In the 1940s, new laws were passed to allow Chinese children to attend white schools (keep in mind that the Brown v. Board of Education ruling didn’t come until 1954). By “accepting” Chinese people into their communities and institutions (“accepting” seems to be a very generous word…), whites could justify continued exclusion of black people, and use their supposed biological or cultural deficiencies to explain away their poverty. Sound familiar?

To be clear, I’m not criticizing early Chinese immigrants for wanting more for their children. In fact, I’m inspired by the ways in which they were able to carve an identity beyond “coolies” in an era that was deeply rooted in systemic racism of all “colored” folk. However, I think it’s important, so important, to acknowledge the ways in which whites with social, cultural, and actual capital created a conflict between Chinese and black communities from the very beginning in order to further the notion and practice that black lives don’t matter. Depressingly, many of these tensions continue to exist between our communities.

Korean-Americans are also often pitted against our black brothers and sisters to further prove some inaccurate cultural deficiency of blackness. But how can we as Korean-Americans, as Asian-Americans, try to understand that we are also responsible for the oppression of Others? How can we concede to the logic of, “look, we made it, why can’t you?” when we do not personally understand the long-lasting impact of slavery, or know what it feels like to be policed as a teen, or have to acutely comprehend that society would rather jail us than educate us? How can we utilize our identities and privileges to not only find our power, but also the power of other people of color? Perhaps, this is what I need to do to be a good Korean-American: to locate my identities, powers, and privileges, and to strategically use them in service of collective empowerment. I don’t exactly know what this means, yet. As of now, I only have my feelings and food. But I’m working on it.

And now, a recipe for salt & pepper shrimp, a relatively classic Cantonese dish:

Salt and Pepper Shrimp Recipe

Recipe taken from The Woks of Life

Prep time: 30 minutes

Cook time: 15 minutes

Ingredients

For the salt and pepper mixture:

2 parts whole peppercorns

1 part sea salt

For the rest of the dish:

1 pound large shrimp, shells on and deveined (with or without heads)

3 tablespoons potato starch or cornstarch

1/3 cup oil for shallow frying

salt and pepper mixture, to taste

6 cloves garlic, finely chopped

1 long hot green or red pepper, thinly sliced

1 scallion, chopped

Instructions

To make the salt and pepper mixture:

- In a small pot over medium low heat, dry roast the whole peppercorns of your choice for 15 minutes, until very fragrant. Take care not to burn them, adjusting the heat as needed. Cool completely and use a spice grinder or mortar and pestle to grind the peppercorns down to a powder.

- In the same pot over medium heat, dry roast the salt until it turns slightly yellow in color. Let it cool and combine it with the ground pepper. You now have your own authentic salt and pepper powder, which you can use in whatever “salt and pepper” dish you like. The rest of the recipe is really easy.

To prepare the dish:

- Rinse the shrimp and pat them thoroughly dry with a paper towel. Dredge them in potato starch or cornstarch––whatever you’re using.

- Heat the oil in a small cast iron skillet to 375 degrees. Quickly lay the shrimp in the oil with about an inch of space in between each shrimp, and fry the shrimp in batches, cooking each side for 30 seconds. Set aside on a paper towel-lined plate, and sprinkle with salt and pepper powder to taste.

- In the wok, heat 2 tablespoons of oil over medium heat. Fry the garlic until just golden brown (careful not to burn it!), and set aside to drain on a paper towel lined plate.

- Remove any excess oil from the wok, so there’s only a tablespoon or so left (you don’t want to use too much oil at this stage, as this is a “dry” dish). Add the peppers to the wok. Turn off the heat, and add the garlic back to the wok, stir-frying everything together for a minute. Add the shrimp to the wok, and gently toss everything for 10 seconds, sprinkling over a bit more of your salt and pepper mixture. Serve!

Coming up…Meal Planning 101: On Cooking with Limited Time and Energy